What’s New in Swift From WWDC 2020

A detailed look at all that Apple unveiled this year

Internal Benchmark: Binary Size

To track progress, we’ve been using a Swift rewrite of one of the apps that ships with iOS.

At each subsequent release, we narrowed the difference. With Swift 5.3, we’re down to below 1.5x the code size of the Objective-C version.

Different styles of applications, however, produce different binary sizes.

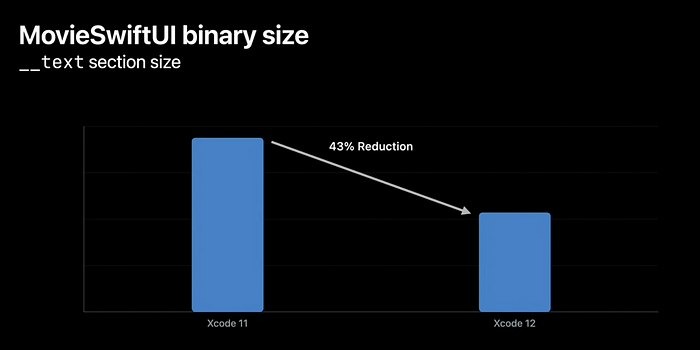

MovieSwiftUI Binary Size

In Swift 5.3, there are significant improvements to the code size of SwiftUI apps. We see that its application-login code size is reduced by over 40%.

Now, binary size is essential for things like download times. But when you’re running the app, it’s part of what we call clean memory. That’s memory that can be purged because it can be reloaded when needed. So it’s less critical then dirty memory, the memory the application allocates and manipulates at runtime.

Dirty Memory

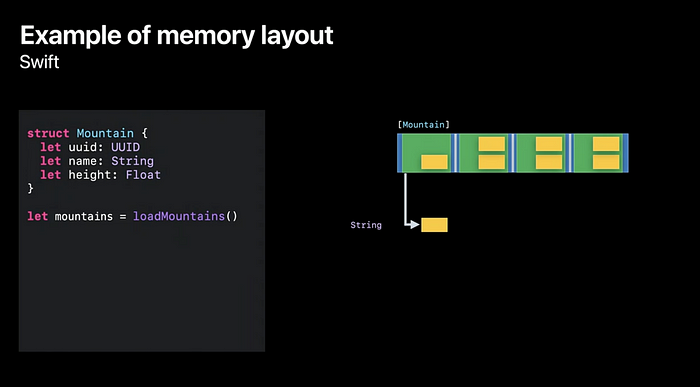

Example of memory layout

Objective-C

Swift’s use of value types has some fundamental advantages over reference type–based languages.

In Objective-C, object variables are just pointers. So the array holds pointers to the model objects. Those objects, in turn, hold pointers to their properties. Every object you allocate has some overhead and performance and memory use.

This is so important that Objective-C has a special, small-string representation for tiny ASCII strings that allow them to be stored within the pointer, which saves on allocating the extra object.

Swift

Swift’s use of value types avoids the need for many of these values to be accessed via a pointer. Thus the UUIDs can be held within the Mountain objects, and Swift’s small string can hold many more characters, up to 15 code units, including non-ASCII characters.

Finally, all the Mountain objects can be allocated directly within the array storage. So with the exception of a few strings, everything is held within a contiguous block of memory. Swift programs can get a significant memory benefit from using value types like this.

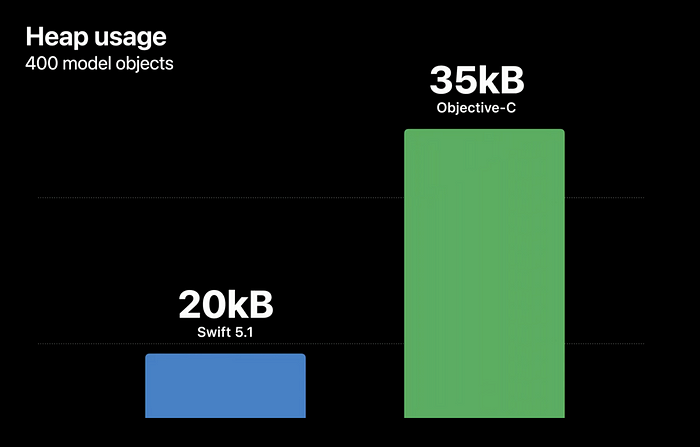

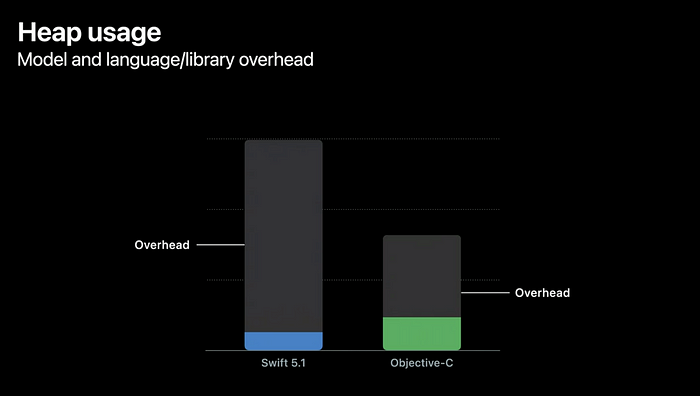

Heap Usage

400 model objects

So if we examine the heat memory used by an array of 400 of these model objects, we can see the Swift model data is more compact.

Model and language/library overhead

Some Swift programs previously still use more heat memory because of runtime overhead. Previously, Swift created a number of caches and memory on startup. These caches stored things like protocol conformists and other types of information as well as data used to bridge types over to Objective-C.

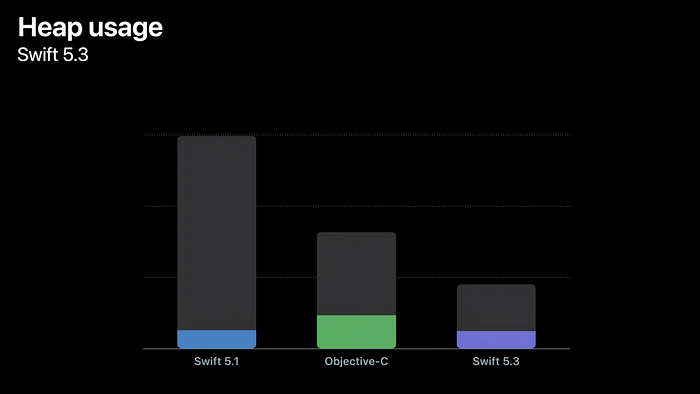

Swift 5.3

All language runtimes have some overhead, but in Swift’s case, it was too large. In Swift 5.3, that overhead has been cut way down to the point where the Swift version of the app now uses less than a third of the heat memory it did in last year’s release.

To get the full advantage of these improvements, an app’s minimum deployment target needs to be set to iOS 14.

Lowering the Swift runtime in the userspace stack

In most applications, these differences aren’t often noticeable, but optimizing Swift’s memory like this was critical to push Swift further throughout Apple’s system — to be able to use it in demons and low level frameworks, where every byte of memory used counts.

Swift’s Standard Library now sits below Foundation in the stack. That means it can actually be used to implement frameworks that’ll float below the level of Objective-C where previously C had to be used.

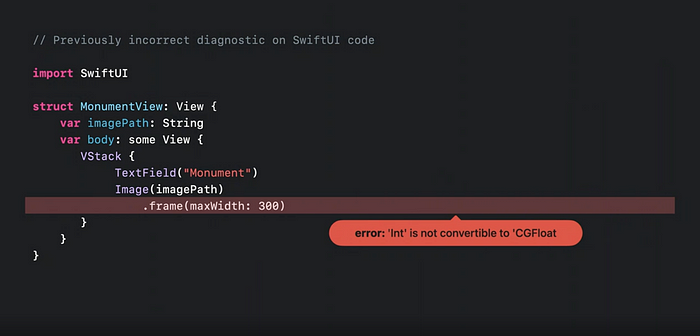

Diagnostics

Errors and warnings from the compiler have vastly improved in this release cycle.

New diagnostics subsystem in the Swift compiler

The Swift compiler has a new diagnostic strategy that results in more precise errors that point to the exact location in the source code where the problem is occuring. There are new heuristics for diagnosing the cause of issue that lead to actionable errors with guidance on how to fix issues.

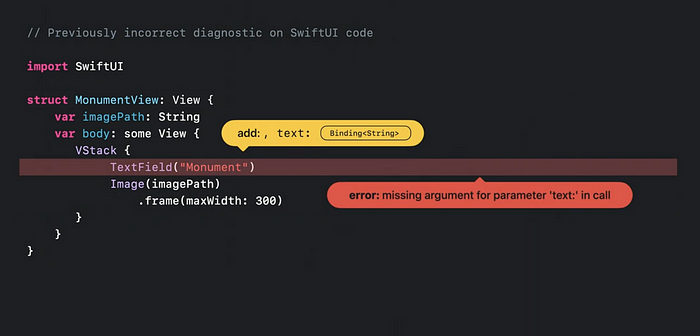

Here’s an example of an incomprehensible diagnostic that the Swift 5.1 compiler would’ve produced in SwiftUI code a year ago.

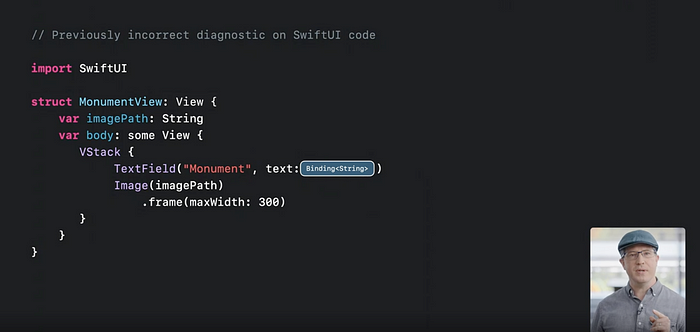

Fast forward to today, and the diagnostic is significantly better with an error that tells you exactly what the problem is.

When diagnosing issue, the compiler internally also records more information about problems, so it now produces additional notes.

In this case, applying the fix naturally guides the developer into providing the missing pieces to an incomplete initialization of a TextField.

Code Completion

This covers everthing from the code-completion inference provided by the compiler in SourceKit and to the experience in the Xcode code editor.

Improved type-checking inference

First, the inference of candidate completions has significantly improved. Here, the compiler is inferring the value in a ternary expression when used within an incomplete dictionary literal.

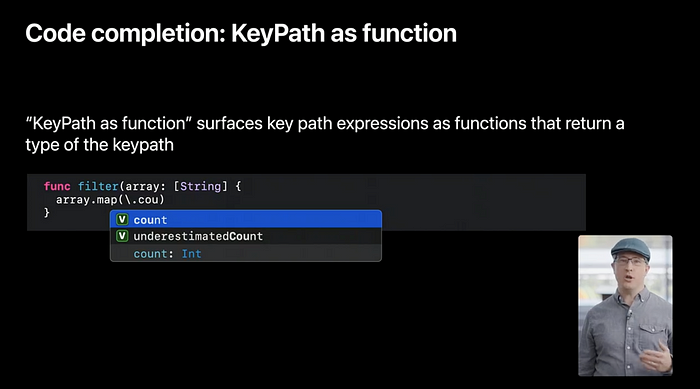

Code completion: KeyPath as function

Code completion also provides the values you’d expect for some of the more dynamic features of the language, such as using KeyPath as a function.

15x faster code-completion speed compared to Xcode 11.5

Besides the quality of completion results, code-completion performance has drastically improved, in some cases up to 15x.

Code completion performance on SwiftUI code

This is particularly beneficial for editing SwiftUI code.

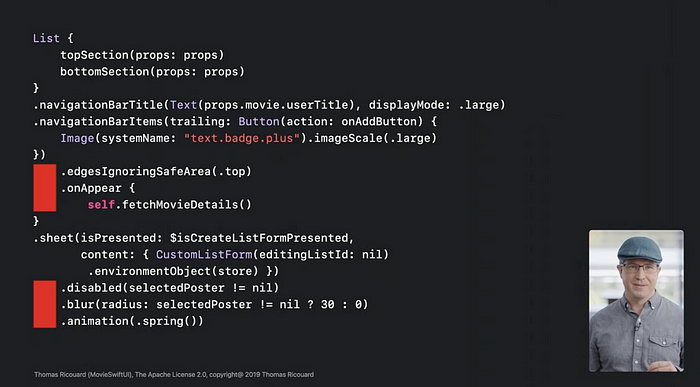

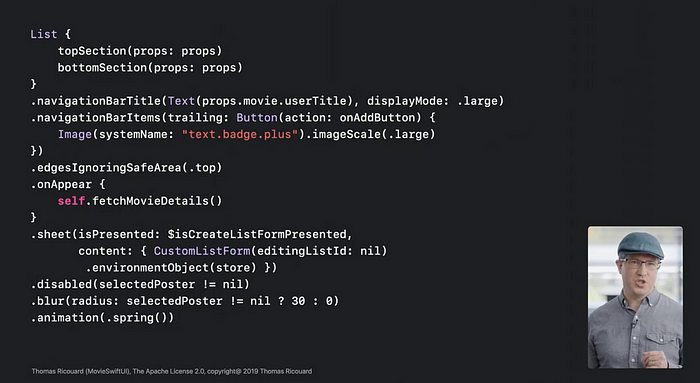

Code Indentation

Code indentation in Xcode, also powered by the open-source SourceKit engine, has significantly improved.

Here, you can see one of the improvements at work in SwiftUI code taken from the open-source MovieSwiftUI project. Before you’d sometimes get a natural indentation for some of the chained accesses.

But now, they’re cleanly visually aligned. These and the other improvements will have a noticeable effect on your editing experience.

Debugging

Better error messages for runtime failures

When debug information is available, the debugger will now display the reason for common Swift runtime failure traps instead of just showing an opaque invalid instruction crash.

Increased robustness in debugging

The pros and cons of using modules for debugging

- LLDB uses Clangemodules to resolve types

- LLDB can encounter different module failures than at compile time

Swift imports APIs from Objective-C using Clang modules. To resolve information about types and variables, LLDB needs to import all Swift and Clang modules that are visible in the current debugging context.

While these module files have a wealth of information about types, since LLDB has a global view of the entire program and all of its dynamic libraries, importing Clang modules can sometimes fail in ways they wouldn’t at compile time — e.g., when the search pass from different dynamic libraries are in conflict.

Using DWARF debug information for Objective-C types in Swift

- LLDB now can resolve Objective-C types in Swift using debug information

- Increases reliability of core debugging features, like Xcode’s variable view

As a fallback, when this occurs, LLDB can now also import C and Objective-C types for Swift debugging purpose from DWARF debug information. This vastly increases the reliability of features such as the Xcode variable view and expression evaluator.

Official Swift Platform Support

- Apple platforms

- Ubuntu 16.04, 18.04, 20.04

- CentOS 8

- Amazon Linux 2

- Windows (coming soon!)

With these efforts comes an increased opportunity to use Swift in more places.

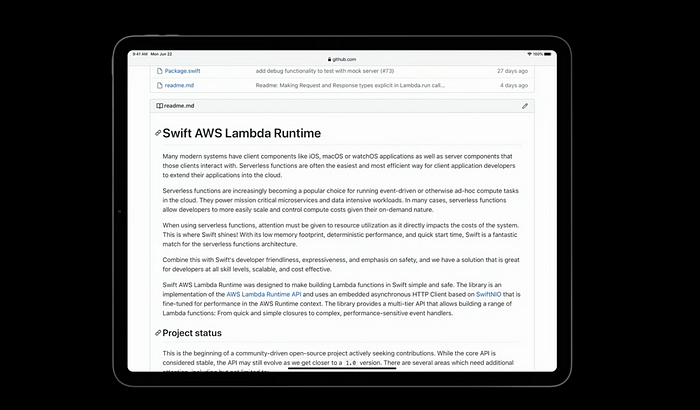

Swift on AWS Lambda

Serverless functions are an easy way for client application developers to extent their applications into the cloud.

It’s now easy to do this in Swift using the open-source Swift AWS runtime.

import AWSLambdaRuntimeLambda.run { (_, evnet: String, callback) in

callback(.success("Hello, \(event)"))

}

The amount of code needed is as simple as writing “Hello, World!”

Language and Libraries

Language

Multiple trailing closure syntax (SE-0279)

// Multiple trailing closure syntaxUIView.animate(withDuration: 0.3, animations: {

self.view.alpha = 0

})⬇️⬇️⬇️UIView.animate(withDuration: 0.3) {

self.view.alpha = 0

}

Since its inception, Swift has supported something called trailing closure syntax that lets you pop the final argument to a method out of the parentheses when it’s a closure.

It can be more concise and less nested without the loss of clarity, making the call site much easier to read.

However, the restriction of trailing closure syntax to only the final closure has limited its applicability.

UIView.animate(withDuration: 0.3, animations: {

self.view.alpha = 0

}) { _ in

self.view.removeFromSuperview()

}In this case, the trailing closure makes the code harder to read because its role is unclear. Worse, it changes meaning from the completion block at one call site to the animation block at another.

Concerns about call-site confusion have led Swift style guides to prohibit the use of trailing closure syntax when a method call, like this one, has multiple closure arguments.

UIView.animate(withDuration: 0.3, animations: {

self.view.alpha = 0

}, completion: { _ in

self.view.removeFromSuperview()

})UIView.animate(withDuration: 0.3) {

self.view.alpha = 0

}

⬇️

UIView.animate(withDuration: 0.3, animations: {

self.view.alpha = 0

}) { _ in

self.view.removeFromSuperview()

}

As a result, if we ever need to append an additional closure argument, many of us find ourselves having to rejigger our code more than may seem necessary.

SE-0281

UIView.animate(withDuration: 0.3) {

self.view.alpha = 0

}

⬇️

UIView.animate(withDuration: 0.3) {

self.view.alpha = 0

} completion: { _ in

self.view.removeFromSuperview()

}New to Swift 5.3 is multiple trailing closure syntax. This extends the benefits of trailing closure syntax to calls with multiple closure arguments, and there’s no rejiggering required to append an additional one.

Multiple trailing closure syntax is also a great fit for DSLs. SwiftUI’s new Gauge view is used to indicate the level of a value relative to some overall capacity.

By taking advantage of multiple trailing closure syntax, Gauge is able to elegantly, progressively disclose is customization points.

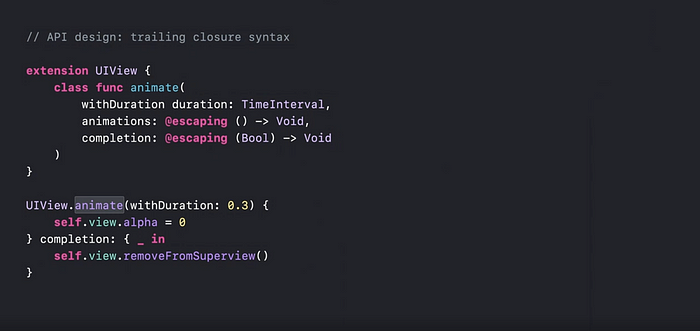

API design: trailing closure syntax

// API design : trailing closure syntaxextension Collection {

func prefix(while predicate: (Element) -> Bool) -> SubSequence

}message.body = "Hello WWDC!\n--Kyle"

let summary = message.body.prefix { !$0.isNewline }

assert(summary, "Hello WWDC!"

A better name for take might be something like prefix, which suggests the result is anchored to the start of the collection.

It’s important that the base name with a method clarify the role of the first trailing closure because its label will be dropped even if it isn’t the first argument to the method.

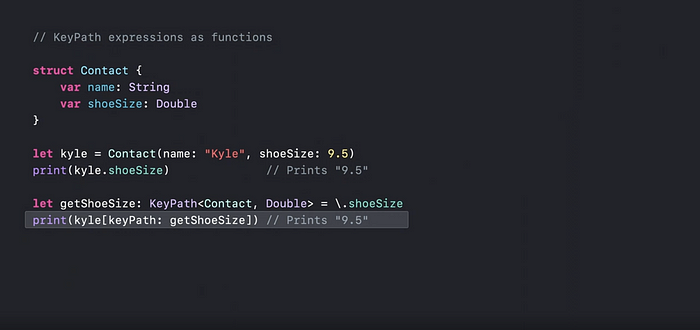

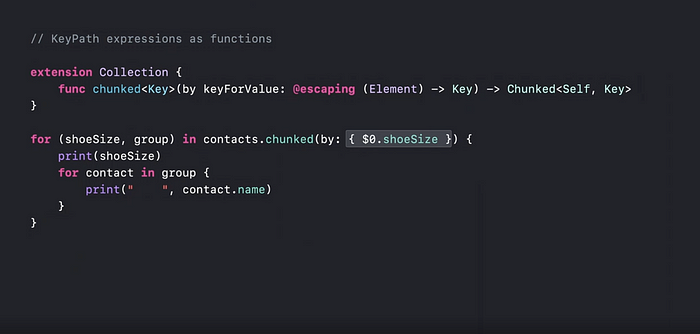

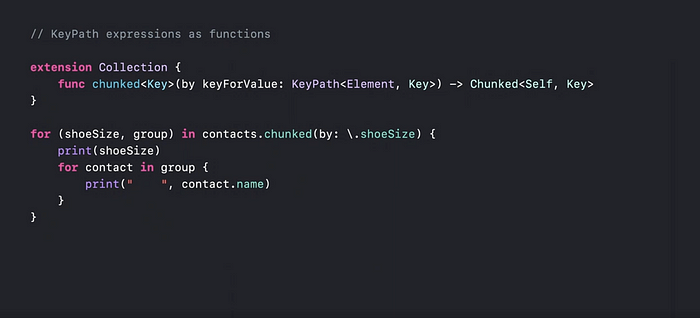

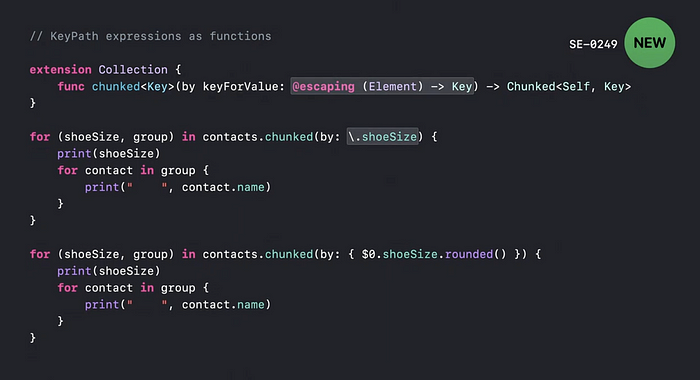

KeyPath Expressions as Functions (SE-0249)

Swift 4.1 saw the introduction of smart KeyPaths: types that represent uninvoked references to properties that can be used to get and set their underlying values.

⬇️

When you’re designing an API, KeyPaths are a tempting alternative to function parameters if you expect the call site to be a simple property access because they’re more concise and less nested.

⬇️

You can use a KeyPath expression as a function. This means you can pass a KeyPath argument to any function parameter with a matching signature, and you can delete any duplicate declarations you may have added in the past in order to accept KeyPaths.

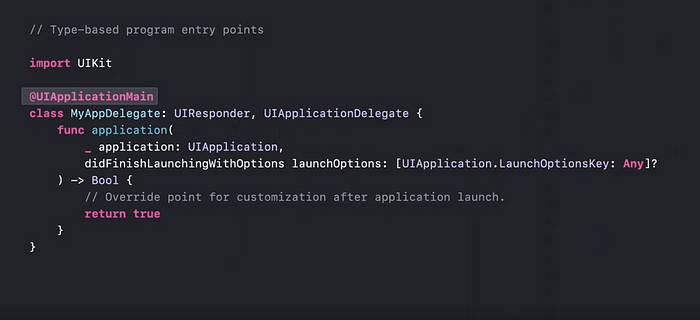

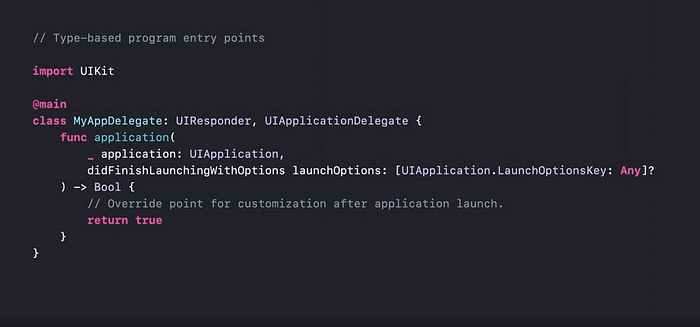

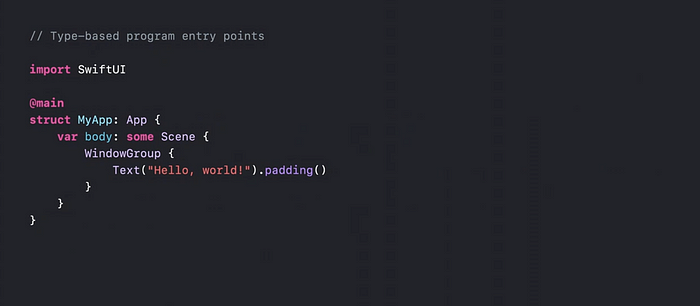

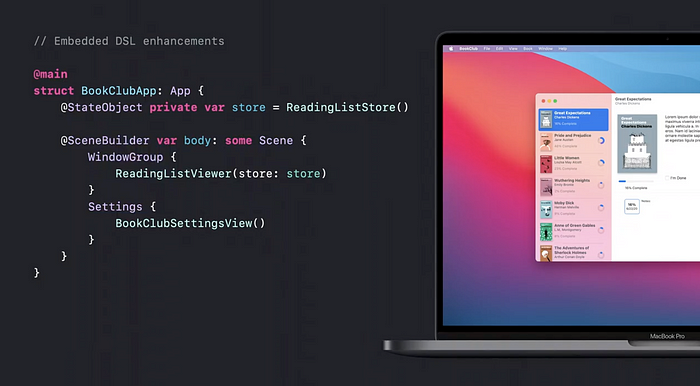

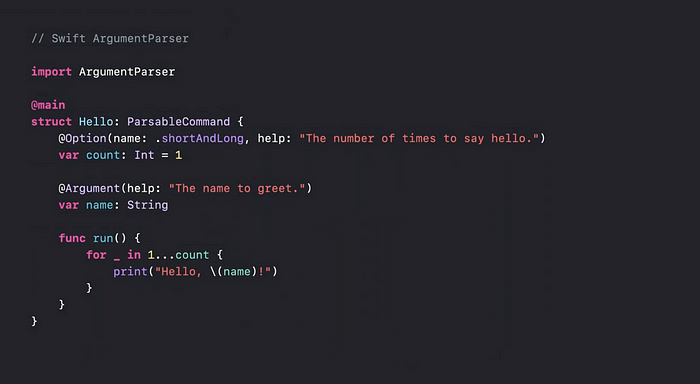

@main (SE-0281)

A tool for type-based program entry points.

Since Swift 1.0, you’ve been able to use the UIApplicationMain attribute on your app delegate to tell the compiler to generate an implicit main.swift that runs your app.

In Swift 5.3, this feature has been generalized and democratized.

If you’re a library author, just declare a static main method on the protocol or superclass you expect your users to derive their entry point from.

This will enable your users to tag that type with @main and the compiler to generate an implicit main.swift on their behalf.

This standardized way to delegate a program’s entry point should make it easier to get up and running, whether you’re working on a command-line tool or an existing application.

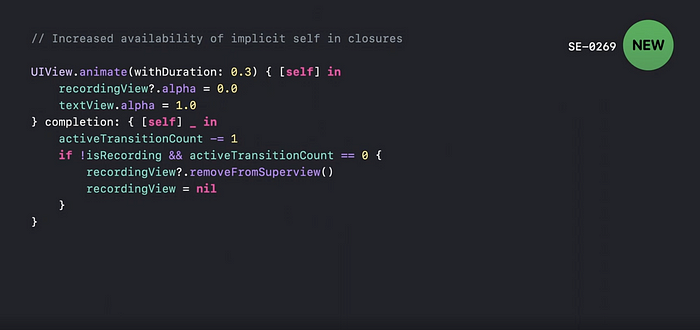

Increased Availability of Implicit ‘self’ in Closures (SE-0269)

In order to dray attention to potential retain cycles, Swift requires the explicit use of self in escaping closures which capture it.

But when you’re required to include many self dots in a row, it can start to feel a bit redundant.

In Swift 5.3, if you include self in the capture list, you can omit it from the body of the closure.

You’re still required to be explicit about your intention to capture self. But now the costs of that explicitness is only a single declaration.

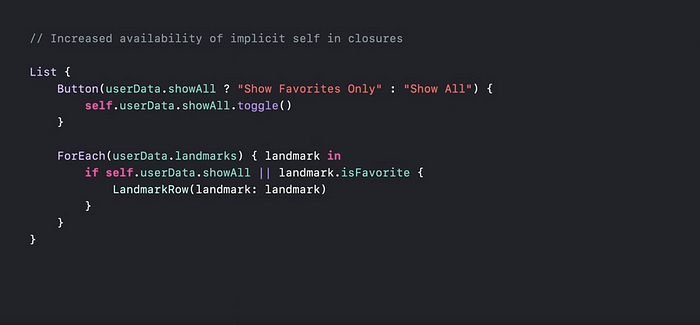

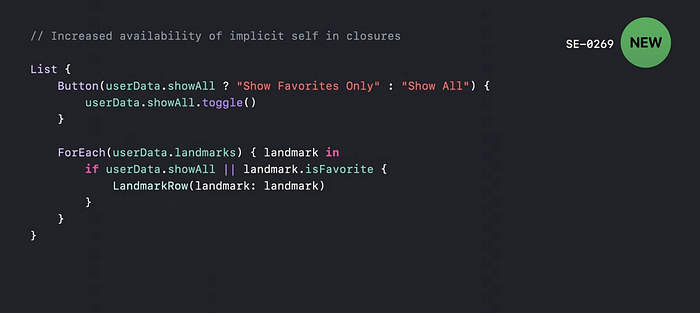

Sometimes, however, even a single use of self. can feel unnecessary — like in SwiftUI, where self tends to be a value type, making reference cycles much less likely.

With Swift 5.3, if self is a struct or an enum, you can omit it entirely from the closure.

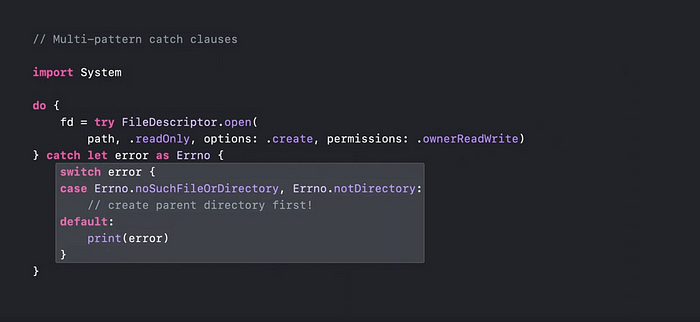

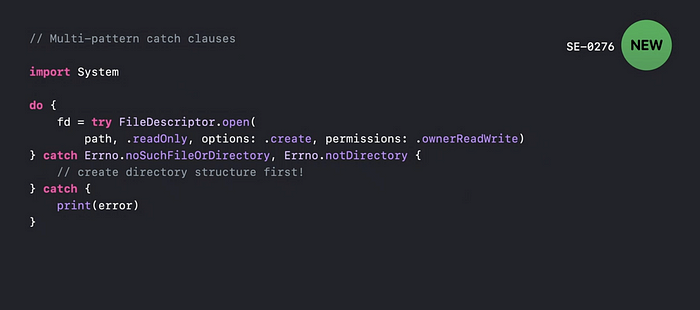

Multipattern Catch Clauses (SE-0276)

Historically, do catch statements haven’t been as expressive as switch statements, leading folks to resort to nesting switches inside of catch clauses.

In Swift 5.3, the grammar of catch clauses have been extended, providing for the full power of switch cases. This allows you to flatten the kind of multiclause pattern matching directly into the do catch statement, making it much easier to read.

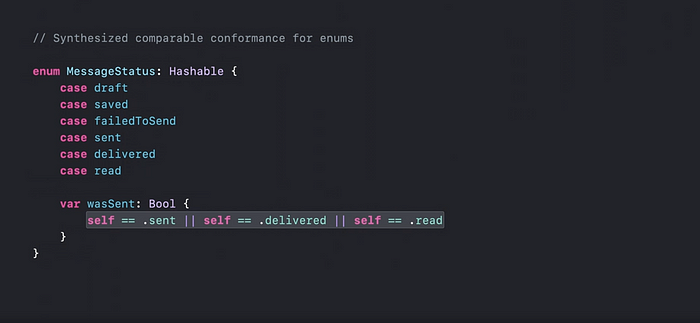

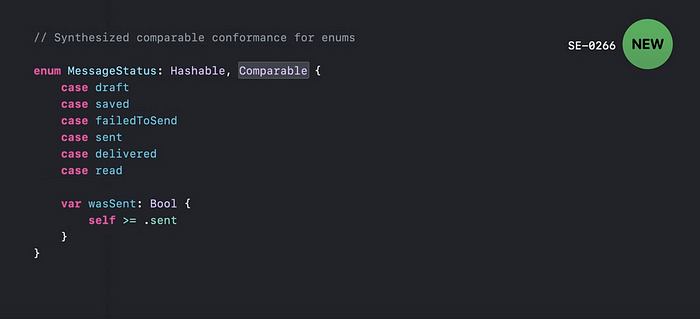

Enum Enhancements

Since Swift 4.1, the compiler’s been able to synthesize equatable and hashable conformance for a wide variety of types.

Sometimes, though, you run into situations where it’d be awfully convenient to have a comparison operator.

In Swift 5.3, the compiler has learned how to synthesize comparable conformance for qualifying enum types.

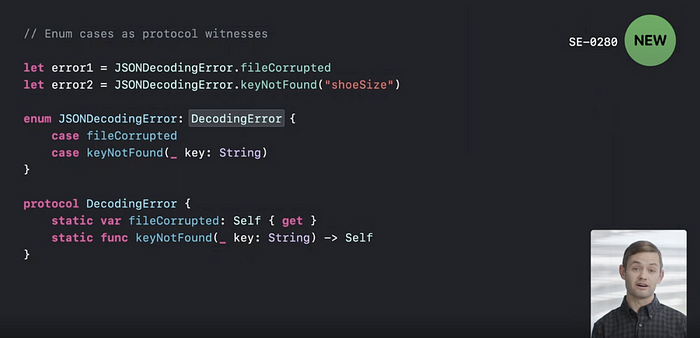

Enum cases as protocol witnesses

In Swift 5.3, enum cases can now be used to fulfill static var and static func protocol requirements.

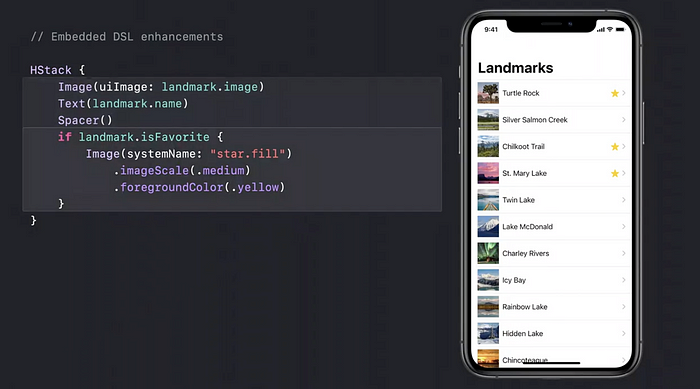

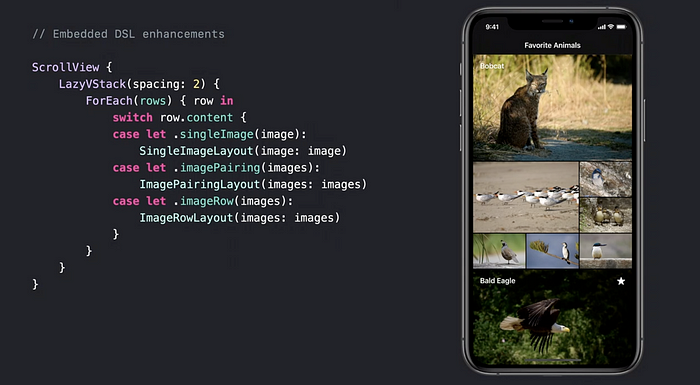

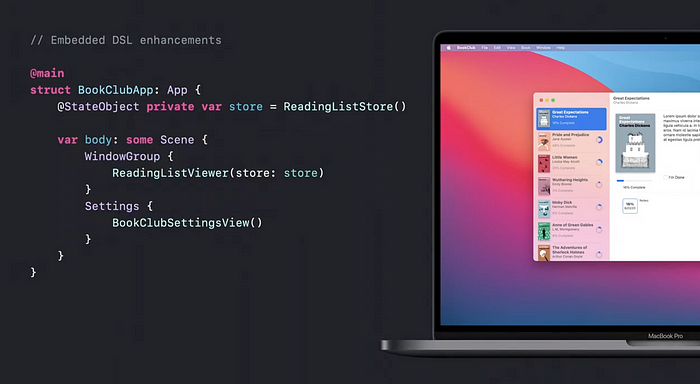

Embedded DSL Enhancements

This included builder closures to collective use children and basic control flow statements like if/else.

In Swift 5.3, embedded DSLs have been extended to support pattern matching–control flow statements like if let and switch.

I’ve got a main window for my primary user interface and a preference window for my app settings.

Previously, to use DSL syntax at the top level of the body like this required tagging it with the specific builder attribute.

In Swift 5.3, the builder attribute will no longer be required because we’re teaching the complier how to infer it from the protocol requirement.

SDK

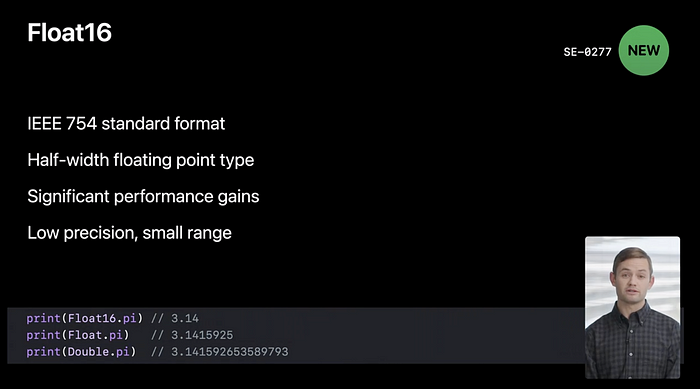

Float16

Float16 is an IEEE 754-standard floating-point format. Float16 takes just two bytes of memory, as opposed to a single precision float which takes four.

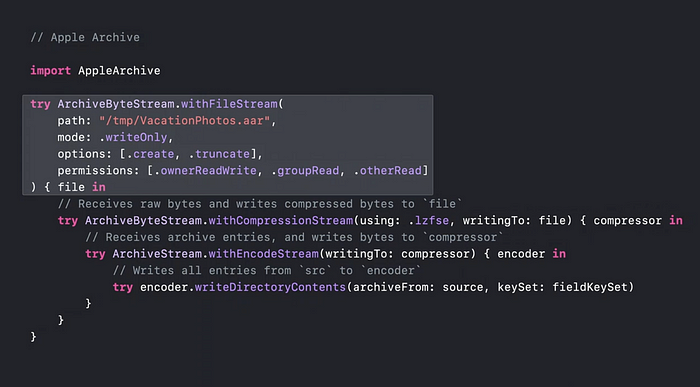

Apple Archive

A new modular archive format based on the battle-tested technology Apple uses to deliver OS updates is here.

Idiomatic Swift API

This includes a FileStream constructor, which leverage another new library, Swift System.

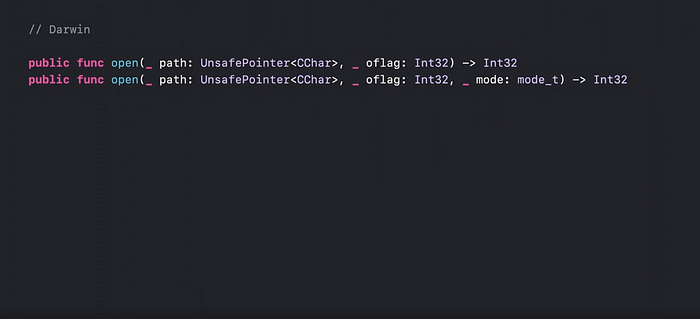

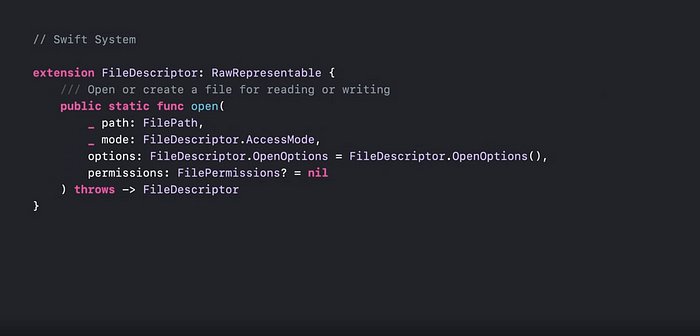

Swift System

The raw, weakly typed interfaces imported though the Darwin overlay can be finicky and error-prone.

Swift System wraps these APIs using techniques such as strongly typed RawRepresentable structs, error handling, defaulted arguments, namespaces, and function overloading, laying the groundwork for a more idiomatically Swift system layer of the SDK.

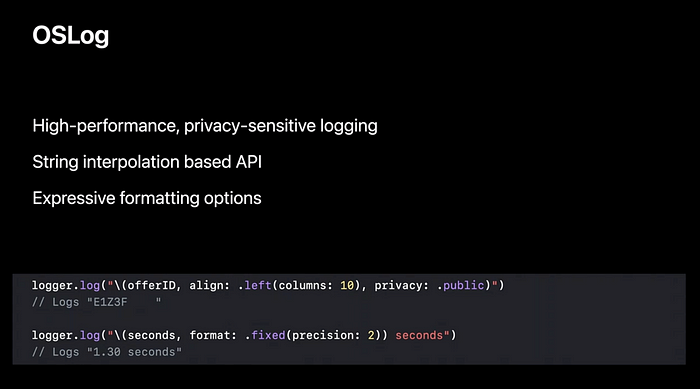

OSLog

If you’re still using print as your logging solution, now is the perfect time to reconsider.

Packages

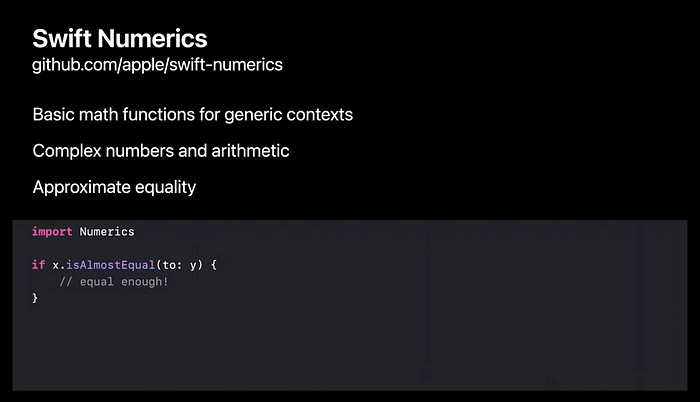

Swift Numerics

Swift Numerics’ complex numbers are layout-compatible with their C counterparts but faster and more accurate.

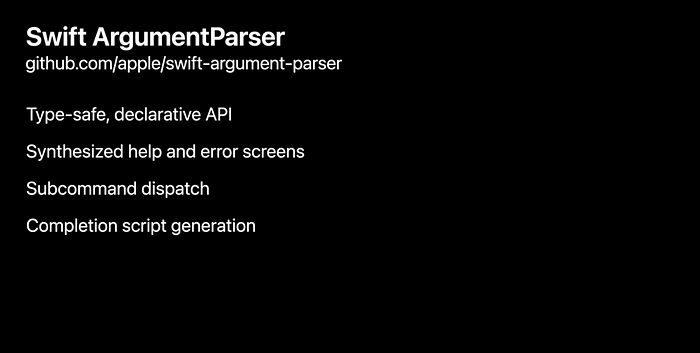

Swift ArgumentParser

A new open-source Swift package for command-line argument parsing.

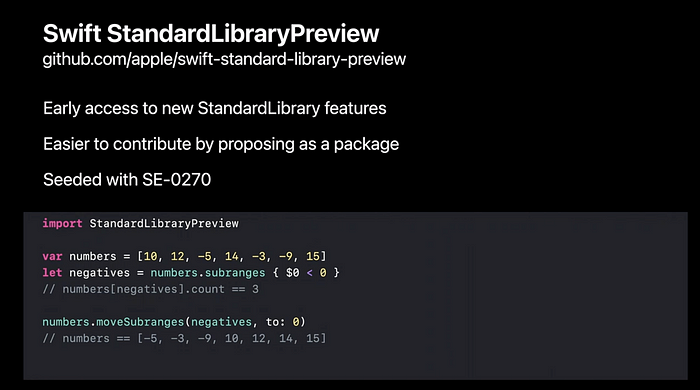

Swift StandardLibraryPreview

Now, you can provide the implementation for StandardLibrary feature proposal as a standalone SwiftPM package.